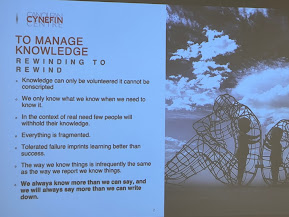

Going Back to Dave Snowden’s Seven KM Principles

1. Knowledge can only be volunteered, it cannot be

conscripted

The sharing

of knowledge is inherently a human behavior. Yet it only happens when we are

intrinsically invested in the positive impact that the sharing of our knowledge

has on the receiving end (because we want to help, because we get nice

feedback, because we want to build relationship, because it might help

ourselves in the future, etc.). If we are told by someone else that we must share

a particular knowledge, there is automatically a loss of quality, because we

have no actual stake in the outcome of the knowledge sharing process. So the

piece of knowledge that is shared is of lower quality, which inevitably leads

to lower adoption and ultimately to lower impact (or no impact at all). This is

maybe the most important KM principle of all, yet organizations unfortunately

ignore it all the time when they create mandatory knowledge transfer processes,

databases of lessons learned or force individuals into regulated knowledge exchange

formats and groups. Instead, we must work with the intrinsic motivation of

people to be of help to others, to achieve impact, to get acknowledged as

experts, get elevated in their status or be rewarded for the good work they do.

2. We only know what we know when we need to know

it.

The effort

to document every bit of knowledge in advance is a huge waste of resources. The

reason is that it is impossible to know ahead of time which parts of all our

potential knowledge will be actually useful to someone else in a specific

situation. “With high abstraction and

high codification, you get rapid diffusion, yet the knowledge remains

superficial. With low abstraction and low codification, diffusion becomes

difficult, but the knowledge is actually denser.” And whether we can afford

to go the path of low abstraction depends on the context one is in. In a

specialized group with experts in a topic, another expert can convey more deep

knowledge in 2 min than what he could communicate in 6 min to a laymen’s group,

because there is a common reference based and a common knowledge around the

topic. That’s why silos exist in the first place. Because it is more economic (in

terms of effort) to focus on knowledge transfer just within silos. One way then

to handle knowledge transfer across silos then is either through metatdata (so

people can find things without having to know the professional lingo). The

other way is to foster the emergence of informal communities, which leads us to

the next principle.

3. In the context of real need few people will

withhold their knowledge.

Which is

why we have to be careful in formalizing and putting mandatory elements around

communities. We don’t create healthy communities by building formal

constructs in which networking must happen in this or that way. We must

stimulate the formation of informal communities, and those

informal communities which stabilize we then re-enforce so they can thrive. So we

shouldn’t create a predefined set of Community of Practice from scratch,

because the energy cost to do so is massive. We instead stimulate the

environment to see what gets traction and then we enforce and put boundaries in

place and invest more energy in to it in order give them the institutional

support they need.

4. Everything is fragmented.

One of the

reasons social media works is because it is fragmented. People like to share

anecdotes and snippets. “The human brain

evolved to handle fragments and put them together, not to process structured

information.” This is how we humans share knowledge, at the fire place, at

the dinner table, at the coffee machine. And “a cluster of such anecdotes is more valuable than a structured

document”. We must keep this in mind when we encounter tendencies to overly

rely on explicit knowledge encoded in formal documents. Formal documents, while

not without merit in specific situations, are not what is best suited to

diffuse knowledge. We think and communicate primarily in fragmented anecdotes

and snippets, so we need to foster environments where such knowledge fragments

can live and promulgate.

5. Tolerated failure imprints learning better than

success.

“All the stories we tell children as learning

stories around the world are stories of failure, not success.” It’s never ‘Hansel and Gretel had a

plan, went into the woods and know how to get out of it.’ No, its ‘Hansel and

Gretel got lost in the woods and imprisoned by the witch, and had to learn on

the fly how to rectify their mistake.’ The human brain picks up failure faster

than success, because avoidance of failure is a more successful strategy than

the imitation of success. We should build worst practices, not best practices

(which might include fictional stories as well as real-life stories). The principle of loss aversion

popularized by David Kahneman

shows us that humans are biased to value the avoidance of pain multiple times higher

than the prospect of gain. We have to work with that bias in KM as well.

6. The way we know things is rarely the same as

the way we report we know things

We should capture

learning as the learning happens, because a few hours later, we remember the

learning already differently. “If we do a

project retrospective, people who fail in a project will remember the past

completely differently than people who succeed in a project. We adjust our

memory to conform with the reality of the present”. That is important to

know, because so much in KM relies on retroactive reporting, which is almost

certainly wrong and will not repeat itself in the same way. The answer to this

is again the fostering of informal communities, in which experiences can be

talked about and are reflected upon in real-time.

7. We always know more than we can say, and we can

always say more than we can write down.

There is always

a great loss of content and a loss of context when transferring knowledge. It

is much easier to capture a narrative and re-use a narrative e.g. in a best

practice document than to improvise solutions when the situation and context

changes. That doesn’t mean that best (or good) practice documents can’t be

helpful in certain situations. But we must not delude ourselves into thinking this

is the essence of knowledge. The essence most likely got lost along the way,

and we need to find complementary formats and channels through which the

essence of our experiences is shared. This is again a warning of the

overreliance on encoded knowledge in documents.

I always find it helpful to re-phrase and document (ha, the irony!) such pointers for me once in a while, so I can go back to them again and again to remind myself of what not to lose sight of. No matter where we are in our professional journey, it is always useful to hone the basics, lest we get overconfident and complacent. I hope it is helpful to you too.

Comments